Hey, I’m Vikram 👋!

One of my favorite online writers, Venkatesh Rao, recently wrote about the Flaubert Frontier, which describes the need for order in daily life to be original in one's creative work. Due to my recent travels to and from Bangalore, my sense of daily order has fallen to the way side and routines broken. So, instead of writing a heavy technical article, I figured there is another way to deliver useful content. If you like this article, please click ❤️ and share it with someone. Thanks! 🙏

We are having a meetup in San Diego on July 12th! If you’re in the area and are interesting in attending, sign up here!

From my recent podcast interview, 1:1 chats with readers, LinkedIn DMs and emails, I get asked one question a lot:

Is it worth getting a graduate degree (MS/PhD) or should I just get a job?

It is a hard question to answer in general. This week's article is a recounting of my own experience that may give you some data points to base your own decisions on. My focus will be on engineering, but general principles will apply to any field.

In this article, we will discuss:

My graduate school journey

How I benefited from it

Should you get a graduate degree?

Read Time: 10 mins

My grad school journey

I want to give you a brief timeline of what my graduate program looked like, and what I achieved during that time. This is not meant to be a humblebrag. Instead, I want to emphasize that clear direction and intention can really get things done. And some tips on how you can do it too.

I began my Masters program at Texas A&M University in Aug 2006, but it wasn't until about Feb 2007 that I switched to my graduate advisor Prof. Kamran Entesari and defended my Masters thesis in January 2009. In the summers of 2007 and 2008, I was an intern at Texas Instruments in the (now defunct) Wireless Technology Business Unit.

I had already decided that I would continue to my PhD because I knew the allure of a full-time paycheck is something I would not let go later. I was offered a six-figure job offer. Twice. My mentor at Texas Instruments was proud of my decision. His words still ring clear in my head - "Stopping at a Masters will limit your options. You should continue towards a PhD."

Getting a PhD was a bucket list item for me and I adored scientists like Feynman, Dirac, and Schwinger. As a child, Dexter's Laboratory was my favorite cartoon, and I wanted to be like Dexter. I guess I was destined to be a science nerd. Luckily, I also really enjoyed doing research. I figured it would take lesser time if I continued my research towards a PhD. So it was an easy decision in that sense. I wasn't really thinking whether it was a good career move.

I defended my PhD on February 14th, 2011, just about two years after I officially started it, and about 4.5 years from when I started my masters program. You can see my full publication record/rap sheet here.

How I benefited from grad school

If you're looking for a direct answer that it helped me get a better job, or make more money, you won't find that here. The benefits were in other aspects I didn't quite appreciate after until a decade had passed. Here are some things I learned:

Communicating Simply

A simple trick that helped me publish a lot of papers is that I learned to explain the results of my research in simple terms. I used short sentences, minimal jargon and put myself in the reviewers shoes. I made pretty diagrams that were clear and concise. I tried not to leave unexplained loose ends.

My PhD taught me to communicate in a clear fashion and be honest with what I don't understand. Like Feynman said, "The first principle is that you must not fool yourself - and you are the easiest person to fool." If there was something I did not understand, I tried my best to find out. If I made certain design choices in my paper, I explained how/why I made them.

I think some people have the perception that your work should sound complex to be worthy of publication. It's quite the opposite. If anybody reading your paper or thesis is able to clearly understand your work, then you have successfully managed to add to the body of human knowledge.

Project Management

Research is the process of extracting meaning from a nebulous haze of information.

The first step is to look around at what has been done, talk to some people, attend a conference and come up with an idea that you think is an improvement. When you pitch it to your advisor, they are going to ask you what problem it solves, why your approach is different, what are the pitfalls, and so on. It's like pitching a startup idea to an investor. It's a valuable skill to learn.

You will then formulate an action plan to go about implementing your idea and executing it with a defined timeframe. You will have setbacks, failures and backtracks. The project will have its ups and downs, breakthroughs and delays. You learn to deal with all of it. You face the reality of delivering on a project on time.

Finally, you develop a prototype, a theory, or an experiment that tells the world what they have never seen before. You submit your paper for publication and wait. You get harsh feedback from the experts, take it in your stride and resolve them. Now you're left with more questions than you started with.

Rinse and repeat. And you've learned to successfully take a project from inception to completion and you'll do it much faster the next time around.

Efficient Hard Work

I want to make the distinction that I learned to work hard, and efficiently. I spent at least 1.5 years of my PhD only working from 8am to 5pm because I was newly married at the time and I wanted work-life balance.

Although I didn't know it at the time, my approach to work was based on what Cal Newport called a Roosevelt Dash in his book Deep Work. Theodore Roosevelt, the 26th president of the United States, had an amazing array of interests ranging from body building to naturalism. His interests left him very little time to actually focus on academics and therefore he worked on school work for only short periods of time but with blistering intensity.

Here was my strategy: identify a task and give myself a hard deadline that drastically reduces the time usually taken to do such a task. Set a countdown timer and set to work on it. The task needs to be on the edge of feasibility, where the successful completion of the task will require levels of concentration higher than usual.

I also used to maintain a log book that had entries for every hour of my day's work. When I was stuck, I used to take long walks around campus to think about them. When I was finished thinking, I went back into my office to work on them. At the end of the day, it was complete rest and relaxation for the next day's onslaught.

I knew I had to do this only for the course of my graduate work. Today, I would not do this in my day job for fear of burning out. I only save it for emergencies.

Learning How to Learn

Over the years, the greatest benefit of doing a PhD for me was learning how to learn. I told my advisor just before I graduated: From an intellectual standpoint, this is the most fun I'll ever have in my life!

Today I have the confidence that no matter how complex the subject, I'll be able to claw my way back to the basics, build on concepts one piece at a time, and eventually construct a decent understanding of how it all fits together. This newsletter gives me a chance to do this on a regular basis, at least at a superficial level.

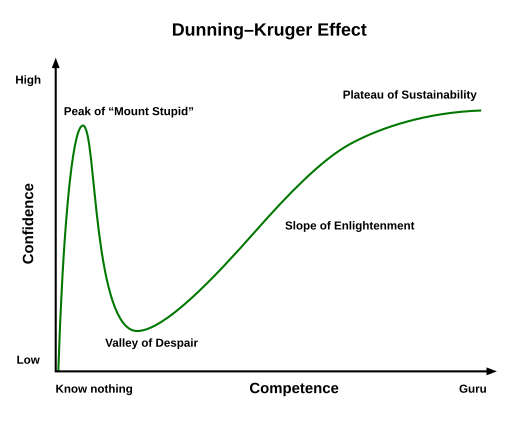

Getting a PhD puts you on the far right of the Dunning-Kruger curve for most (there are exceptions, and I’d rather not get into it. 😆)

Should I do a graduate program?

"Ok that’s nice, but should I do a masters program in engineering or not?"

Short answer: Yes. The extra two years or so you spend doing a good Masters program opens up a world of opportunity in the job market and introduces you to the way industry actually works.

Take for example the analog circuits course I took under Prof. Jose Silva-Martinez. His class covered all the ways real analog circuits and bias blocks were designed in industry. The course labs involved designing a circuit to a given specification, doing IC layout, and running parasitic extractions, all within a tight deadline. I now realize that this was a close emulation of the real world.

I view a good Masters program as an on-ramp to industry. And for many, this is a good place to stop. It gives you good bang for the buck. But should you really do a PhD?

I can't give you a short answer here. This might sound a bit harsh, but I’m going to say it: Unless you plan on academia, a PhD program only makes sense if you can complete it with a reasonable span of time (4-5 years). The reality is that PhDs don't get paid all that much more compared to masters students who joined industry (exceptions apply). And you have 5 years of opportunity cost to recover, which in the field of engineering can mean half a million dollars at least in the US.

Money isn't everything. Doing a PhD opens even more doors to opportunities that take you to the cutting edge of a field. The excitement and satisfaction from a job on the frontier of technology can be fulfilling. Especially in the field of integrated circuits, it is crucial to develop the experience of taping out a chip from concept to implementation. Access to silicon is expensive, and hence most research institutions reserve it for students who really need to publish - the PhD students.

On top of just tapeout experience, industry always wants people who are experts in certain areas of interest. For example, a PhD with published work in power amplifiers will have a much easier time jumping into an ongoing chip design and making valuable contributions. Such a candidate is valuable for a company because they do not bear the cost of training an employee to do exactly what they want. They get an expert-in-a-can.

There are also roles in industry that are heavily geared towards research. These can be exciting positions to work in because you will have the company's extensive resources behind your research to develop the latest and greatest in the industry. Such roles are difficult to break through without sufficient technical background.

Final Thoughts

Plenty of people are wildly successful without going to graduate school and go on to become entrepreneurs and innovators of the highest calibre. I have also worked with people who don't have graduate degrees but still have razor-sharp analysis and technical skills. I have also seen the converse: people with graduate degrees lacking proper reasoning.

While a graduate school program might give you the opportunity to develop some of these skills, it is up to you to take ownership and cultivate a growth mindset for life. Make the proper risk-reward calculations based on your own life's circumstances. You can reap all the benefits I listed even without the rigor of a graduate program, as long as you are intentional about developing them.

The face of education is changing. There are many online learning resources that are low cost, and up-to-date, offering visual learning experiences that most traditional education establishments can only dream to develop, all while education costs are going up.

What do you think of graduate school? Still have questions? Let me know in the comments.

The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in this newsletter are solely mine; they do not reflect the views or positions of my employer or any entities I am affiliated with. The content provided is for informational purposes only and does not constitute professional or investment advice.

An insightful letter without much technical details. Maybe on your next non technical letter, please write about cornering down a single area of interest and more into choosing a guide and research centers for PhD.

This was a great article, Vikram. I've got loads of thoughts and I'll try and summarize a few of them (from the viewpoint of someone who did a Master's and decided against a PhD).

- I totally agree, if you don't believe you will stay in academia, a PhD is probably not worth the time, tuition, and opportunity costs. You likely become over-trained in a small niche, and vastly under-trained in most other areas, and makes you not worth the salary you'd expect.

- As far as a Master's degree, I think I hold a slightly different view. Overall, I believe the extra schooling isn't worth getting unless you know the job you want (e.g., school principal) requires it. Most of the points you mention that made it worth it - communication, efficient work - I believe you can accomplish in a regular job. Arguably, efficient work and communication get better in a normal job I would believe.

- However, learning to learn I think is best done in a university setting where you have a low risk of messing up, and can explore topics or problems you want without much oversight from a boss. This environment is perfect for developing applicable problem-solving skills.

Thanks again for this article and the debate of grad school being worth it or not will always be a tough question for anyone considering it; I appreciate you sharing!