The State-of-the-Art in RF Filter Technology

How acoustic wave and electrical filters shape the spectrum of our wireless world.

Hey, I’m Vikram 👋!

Most of my PhD work at Texas A&M University was about tunable RF filters using MEMS technology, but somehow I never ended up looking in-depth at acoustic-wave filters. I had a lot of fun writing this article, and it’s fascinating to me how these things work. I hope you feel the same awe in it that I did.

If you like this, please click ❤️ on Substack and share it with someone. This is an easy way to support this free publication.

In a previous article, we looked at how the RF front end of any radio receiver properly selects the right signals from a densely crowded frequency spectrum by switching and filtering between hundreds of signal paths. If you haven’t read that one, check it out.

The key to signal selection is to use RF filters, whose function is to let signals of a desired frequency through, while blocking the rest. Filters fundamentally operate by resonating at a particular frequency. Compare it to a playground swing. To make the swing go higher, you have to time the push with the frequency of the pendulum swing. You need to resonate with the frequency of the swing.

Similarly, a correctly designed resonant circuit will allow a signal with the right frequency through, while damping out the others. A quantitative measure of how much signal it lets through compared to how well it damps out unwanted frequencies is called the filter quality (or Q) factor. We want Q-factor to be as high as possible.

Filters in reality are not specific enough to let a single frequency through. There is range of frequencies for which the signal will pass through, called the bandwidth of the filter. The bandwidth requirement will be narrow or wide depending on the wireless standard the filter serves.

Another important thing to know is that the size of the filter is proportional to the wavelength of the signal at resonance.

The most widely used filters for cellular technologies are acoustic wave filters primarily due to their small size and high Q-factor. Acoustic filters are built on special substrates called piezoelectric substrates (commonly Lithium Tantalate, LiTaO3), which convert mechanical stresses to electricity and vice versa. They are highly compact due to the phenomenon of acoustic-resonance at gigahertz frequencies, whose wavelength is in the micron range compared to electromagnetic resonance-based filters whose wavelength is in the centimeter range.

Due to this fact, there was a massive boom in the RF acoustic-wave filtering industry in the last decade or more with the rise of mobile communications, for which size is the primary driving factor.

In this article, we will look at various RF filter technologies including new developments for the future of wireless communications:

Surface Acoustic Wave, with temperature compensation

Bulk Acoustic Wave (FBAR, SMR, CMR, XMR)

LC Filters (LTCC, IPD)

New filters for our wireless future

Read time: 11 mins

Surface Acoustic Wave (SAW) Filters

In the beginning, there were 1G, 2G and 3G phones. They operated at a maximum frequency of about 2 GHz, with a 2G GSM band at 900 MHz and a PCS band at 1900 MHz, while 3G phones used 2100 MHz for Band 1 and 850 MHz for Band 5. SAW filters could achieve quality factors around 800 at these frequencies, which was adequate for mobile communications.

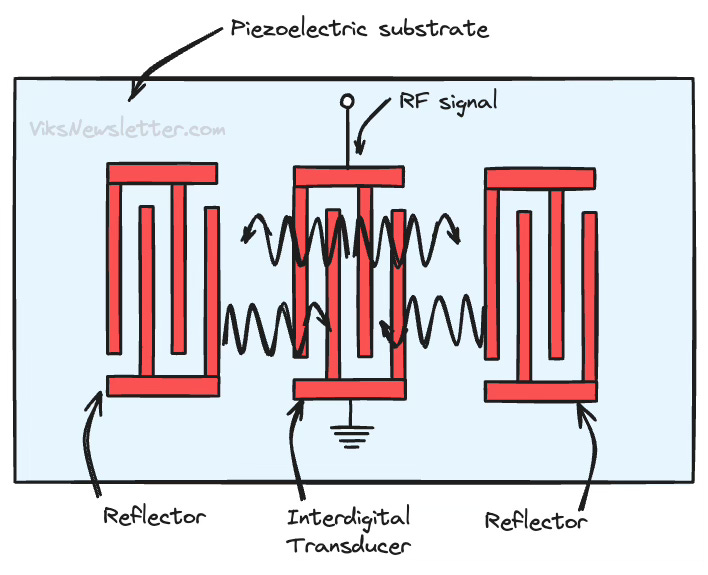

SAW filters are implemented on piezoelectric substrates with strips of aluminum in a hair-comb structure called interdigital transducers (IDT) that converts electrical signals into mechanical vibrations also called acoustic waves. These waves travel laterally along the surface of the piezoelectric substrate, hit other IDTs placed on either side at a strategic distance away and bounce back. Depending on the physical construction of this structure, the SAW filter has a specific resonant frequency.

As the frequency of operation and bandwidth increased in later generations of wireless standards, it became difficult to manufacture SAW filters with narrow aluminum feature sizes on the piezoelectric substrate and achieve filter bandwidths in excess of 100 MHz. Another problem was that the filter performance moved around with temperature, either from external environments or from heat dissipation in the filter.

To overcome these issues, improvements to SAW filter technology was necessary. These improvements were made with a variety of techniques as we will see below.

Temperature-Compensated (TC) SAW Filters

Piezoelectric substrates exhibit a negative temperature coefficient of about -20 ppm/C to -40 ppm/C, which means that the frequency response shifts to lower frequencies as temperature rises. TC-SAW filters overcame the issue of temperature drift using one of two techniques:

Deposit a thin layer of silicon dioxide (SiO2) on top of the IDT structure. The positive temperature coefficient of SiO2 cancels out the negative response of the piezoelectric substrate, effectively delivering a near 0 ppm/C frequency shift. But this results in extra filter losses and spurious resonant modes.

Bond the piezoelectric substrate to another substrate that has a low thermal expansion coefficient, such as sapphire or silicon dioxide. But the temperature stability of this approach is not as good as the previous one.

Temperature stability was a necessary feature for the 4G LTE standard. The fact that Band 40 (2.3 - 2.4 GHz) nearly coincides with the lower edge of WiFi (2.401-2.483 GHz), places harsh requirements on filter accuracy. But as the frequency of wireless standards got higher, the width of the aluminum electrodes in the IDT got smaller and SAW filters soon ran into increased loss and electromigration issues at high transmitter power. While researchers tried a variety of metal alloys to mitigate this issue, it was time for a new technology.

Bulk Acoustic Wave (BAW) Filters

BAW filters solved the problem of scaling to higher frequencies, along with the need for handling higher power. There are two approaches to creating acoustic wave filters that employ the bulk piezoelectric material for resonant phenomena:

Film Bulk Acoustic Resonator (FBAR)

Solidly Mounted Resonator (SMR)

Film Bulk Acoustic Resonator (FBAR)

The working principle of FBAR is simple to visualize. It consists of a piezoelectric material sandwiched by a top and bottom electrode. When an alternating voltage is applied to the electrodes, mechanical strain in the substrate is produced due to reverse piezoelectric effect. This creates an acoustic wave that bounces back and forth between the two electrodes forming a resonator. BAW filters are then made by coupling resonators together.

The "film" in FBAR refers to the fact that the electrodes and piezoelectric substrate are implemented as a thin film that is suspended over a supporting substrate. The supporting substrate is selectively etched away under the piezoelectric material allowing it to vibrate (and resonate) freely. The high acoustic impedance interface between the bottom electrode and air allows acoustic waves to reflect back into the piezoelectric material, forming a resonator.

Using this operating principle and Aluminum Nitride (AlN) as piezoelectric material, Q-factors greater than 2000 could be achieved from 2-8 GHz, which made it an ideal candidate for 4G LTE/5G applications. FBAR is resilient to temperature variations and is process-compatible with CMOS foundries. This made it attractive to commercialize FBAR technology and a number of big players such as Broadcom, Qorvo, STmicroelectronics, Samsung, TDK (Qualcomm), and TAIYO YUDEN got into the game.

The way to increase the operating frequency of FBAR filters is to thin the AlN substrate. For example, by thinning it down to 120nm, an FBAR can be made to work at 24 GHz. Another way to achieve high frequency operation is by using higher order resonant modes with an Overmoded BAW (OBAR) resonator.

The downside of BAW filters is that it is hard to make filters with wide bandwidths. The bandwidth heavily depends on the properties of the piezoelectric material. In efforts to increase bandwidth, researchers have successfully doped AlN with scandium which resulted in over 2x improvement in bandwidth. A strongly piezoelectric material such as Lithium Niobate (LiNbO3 or LN) has also shown promising results.

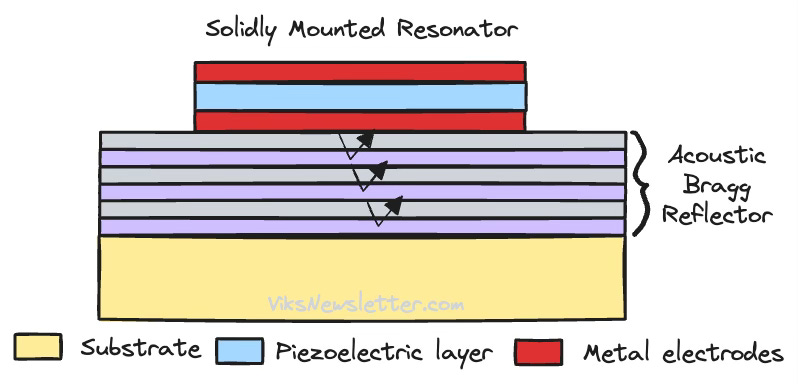

Solidly Mounted Resonator (SMR)

The essence of FBAR is in having a high impedance between the electrode and air interface so that the acoustic wave can be reflected back into the resonator. The same effect can be achieved instead by placing what is called a acoustic Bragg reflector under the piezoelectric material with top and bottom electrodes.

An acoustic Bragg reflector contains an alternating series of high impedance and low impedance layers (tungsten and silicon dioxide, for example) so that at every interface part of the signal is reflected back. The more layers in a Bragg reflector, the higher the impedance presented by the reflector due to multiple reflections. By placing a Bragg reflector under the bottom electrode of a BAW resonator, the signal is reflected back into the piezoelectric material causing resonance.

SMR BAW filters are capable of great performance. For example, Qorvo reported an SMR filter that can handle 5W of RF power with 40W peaks. Recently, they also reported a new type of SMR BAW filter that uses scandium doping and supports operation from 1-8 GHz, covering 5G and WiFe 6E bands.

Contour-Mode Resonator (CMR) and XMR

With FBAR and SMR BAW filters, only one resonance is possible based on physical structure, which means a different filter chip is required for each band of operation. With the rapid increase in cellular bands, there is a need to implement multiple bands of operation on a single BAW chip. Contour-Mode resonator (CMR) BAW technology was developed for multi-band operation.

The physical structure of a CMR BAW resonator is a mix of IDT structures used in SAW filters with a bottom electrode used in BAW filters. The result is that multiple modes of resonance can be excited in both the lateral (along the surface like in SAW) and vertical (like in BAW) directions enabling simultaneous modes of resonance, at different frequencies. This enables the design of a multi-frequency BAW resonator that can handle multiple bands at once.

In FBAR, SMR and CMR, getting wide filter bandwidths is always an issue due to limited coupling coefficients. In order to increase coupling and hence filter bandwidths, researchers discovered ways to combine multiple modes of operation together. Instead of purely designing resonator metal shapes from a birds eye view, researchers designed the resonator by looking at its cross section and associated modes. By sophisticated design of BAW filter electrodes, a new class of BAW filters called XMR was developed for wide bandwidths. This class of filter is very new and is still under research development.

Lumped Element Filters

As we enter the 5G-new radio (NR) era, the bandwidths of the n77-n79 bands compared to previous generations is ten-fold larger. SAW and BAW technologies have always had issues with wide bandwidths due to relatively low coupling through piezoelectric materials.

To solve this problem, today's 5G smartphones commonly use lumped element LC filters. The inductors (L) and capacitors (C) are implemented on multi-layer substrates such as low temperature co-fired ceramic (LTCC) or integrated passive devices (IPD). The Q-factor of passive devices on such technologies is not high. As a result, these filters do not have good selectivity. This is still tolerated for two reasons:

The 5G frequency band is still not as densely occupied as earlier generations, so the lower selectivity of the filter may be acceptable.

Wide filter bandwidths required for 5G can be implemented. Since SAW/BAW do not work as well in this use-case, there is really no other choice.

The primary downside of using LTCC for filters is that the multi-layer approach to implementing passives results in an overall thickness that is unsuitable for low-profile modern smartphones. In addition, the low tolerances in the manufacturing process does not give good yield.

IPD is much more superior technology especially when implemented on substrates such as glass. The manufacturing tolerances are tighter, thickness is smaller and high density metal-insulator-metal (MIM) capacitors are achievable, resulting in a more compact and tightly controlled filter. If GaAs IPD is used, then there is a possibility of integrating filters with active circuits.

Still, the limited Q-factor and poor selectivity will become an issue in the future with the rise of WiFi 7 and 6G cellular technology. The future needs more sophisticated filters.

Looking Ahead

The future of RF filter technology holds many innovative approaches still under investigation and research. We are nowhere close to having all we need. That being said, here are some exciting developments.

Incredibly High Performance (IHP) SAW: Murata demonstrated a SAW filter that has a Q-factor of over 4000 (>4x than regular SAW) with an operating frequency of over 5 GHz. Various combinations of supporting substrates and piezoelectric materials are being investigated to push the boundaries of performance.

XBAR: Resonant Inc., which was acquired by Murata in 2022 for its proprietary XBAR, a unique combination of SAW and FBAR BAW technologies, promises to deliver acoustic-wave filters for 5G NR applications, including the n79 band.

XBAW: Akoustis is another company that promises high performing, wideband acoustic wave filters for 5G and modern WiFi technologies. They utilize single crystal AlN thin films that provide better piezoelectric properties than their polycrystalline counterparts to develop their proprietary technology.

Hybrid: RF filters of the future might employ a combination of carefully co-designed acoustic and LC filters to achieve the best of both worlds. Published work demonstrates bandwidths of 900 MHz (from 3.3-4.2 GHz), while providing 36 dB rejection at 4.4 GHz (Band n79), only 200 MHz away. This is definitely promising.

Lastly, do watch this awesome video from the Asianometry YouTube channel about SAW and BAW filters and how they were used in various iPhone generations.

References

[1] K. Yang et al., “Advanced RF filters for wireless communications,” Chip, vol. 2, no. 4, p. 100058, Dec. 2023, doi: 10.1016/j.chip.2023.100058. (Link to open download)

The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in this newsletter are solely mine; they do not reflect the views or positions of my employer or any entities I am affiliated with. The content provided is for informational purposes only and does not constitute professional or investment advice.

Great article. I believe there is a typo in "while providing 36 dB rejection at 4.4 GHz (Band n41), only 200 MHz away. This is definitely promising." Should be n79, not n41

One more question if I may.

From filters' perspective, what advantages, disadvantages, challenges or opportunities you foresee if future communication goes to higher frequency bands, e.g. millimeter waves? More specifically, do you think it will become harder or easier to make filters?