Why Fathom Light uses LiDAR in Long Range Airborne Applications

Why it makes sense to use LiDAR technology instead of radar in unmanned drones.

At 2025 SPIE Photonics West Conference recently held in San Francisco, I attended a talk by Fathom Light, a startup working on using LiDAR technology in airborne applications for >1km distances. I found the talk fascinating for a few reasons:

I have only heard of radar for airborne applications. Why has nobody used LiDAR and why is Fathom Light using it now?

LiDAR for automotive applications only has a range of about 300m. Fathom Light’s LiDAR technology works at 5X that distance. How do they do it?

Why do drones benefit specifically from using LiDAR?

Fathom Light has a solid team of innovators which include the ex-CEO and ex-CTO of Velodyne LiDAR (merged with Ouster in 2023), and other experienced professionals from the world of lasers and photonics. For the rest of the team, see here.

Quick note: I wrote this post because I found the technology fascinating. I am not getting compensated by Fathom Light for this post. My research materials were the actual paper by Fathom Light, discussions with their team, and slides that I saw at the talk.

About Fathom Light

Fathom Light is dedicated to developing the highest performance and cost-effective solutions for sensing applications within a 1 to 10 km range. Their enabling core technology consists of an optimized, compact, and affordable laser source coupled with proprietary scanning and detection methods. Their first goal is to produce a cost-effective "See And Avoid" Airborne Collision Avoidance Systems for standard use in air taxis, helicopters, UAS, and other manned and unmanned VTOL platforms. Their system enables a significant decrease in accidents, equipment damage, and loss of life for adopters. Other application marine surface threat detection, surveillance, geospatial and bathymetric mapping, and target tracking.

About Mathew Rekow — Founder and CEO

Mathew Rekow is a veteran of 3 photonics startup companies and former CTO of Velodyne LiDAR. He led the Velodyne team in developing the groundbreaking LiDAR technologies that enabled Velodyne to go public. He has now turned his experience in creating value and technical expertise to create novel sensing solutions for the emerging UAS and eVTOL industry.

Here is what we will cover in this article:

Need for detection in airborne systems

Limitations of radar systems

Pros and cons of LiDAR and radar systems

Making LiDAR work for long range airborne applications

Demonstration of long-range LiDAR detection

Read time: ~11 mins

This post is too long for email. Please read it on the website by clicking on the post title.

This is a free post. Please consider upgrading to a premium tier for more in-depth content.

P.S.: If your startup is doing interesting things in the world of semiconductors, RF, photonics, or power electronics, and you would like your company featured in this newsletter, email me at substack(at)vsekar(dot)com. We’ll talk!

Need for detection in airborne systems

Airplanes and Helicopters

Recent mid-air crashes, such as the tragic collision on January 29, 2025, near Reagan National Airport in Washington, D.C., involving an American Airlines jet and a U.S. Army Black Hawk helicopter, have raised serious concerns about airborne safety. This incident, which resulted in 67 fatalities, is the deadliest U.S. air crash in over 20 years. Just 24 hours before the fatal crash, another regional jet had to abort its landing at Reagan National Airport due to a military helicopter in the area, suggesting a pattern of near-misses that may have been overlooked. Army Air Crews is a website that keeps track of individuals who have lost their lives operating US Army aviation aircraft that includes the recent incident.

Helicopters are contraptions that by themselves have a long history of fatal crashes taking the lives of notable icons such as Stevie Ray Vaughn in 1990 and Kobe Bryant in 2020. Even with three decades separating these incidents, these fatal accidents were chalked out to poor visibility conditions which resulted in the pilots failing to see the hill in front of them. Both pilots were flying with visual guidance and did not use instrument based navigation under poor visibility conditions.

Here is a tweet from a former Blackhawk pilot explaining how it feels like flying a helicopter.

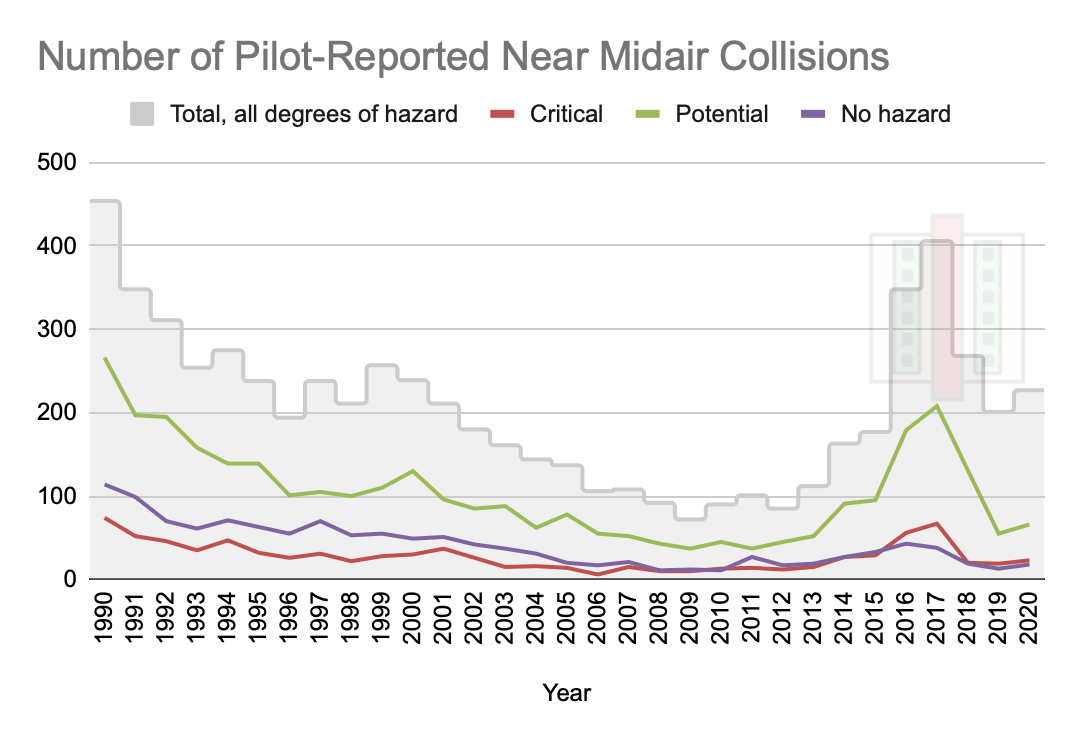

The plot below is a plot of data from the bureau of transportation statistics, which shows the number of near mid air collisions as reported by pilots for the last 30 years. The three classifications shown are:

Critical: <100 feet of aircraft separation, and due to chance rather than pilot error

Potential: <500 feet of aircraft separation, with probability of collision without pilot intervention

No hazard: When direction and altitude would have made a mid air collision improbable regardless of evasive action taken.

These events show that there is a clear need for better airborne detection technology and protocols.

Drones and Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs)

The necessity for autonomous drones, which are increasingly being used for drone deliveries by countries such as China, complicates the safe navigation of airspace. The US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has been cautious to allow large-scale drone deliveries due to the greater danger of interfering with aircraft and helicopters. Even if drones are limited to a maximum altitude of 400 feet, there is a substantial possibility that they would mistakenly enter commercial and military airstrips alongside low-flying airplanes. Drones are considerably more difficult to detect with electrical systems due to their small size, but they can still cause severe damage in crashes.

From the perspective of UAVs, the detection problem is different. Autonomous drone deliveries require the detection of small features such as power transmission lines, fences and other objects near ground level that they must see and avoid. They require compact, power-efficient, and high resolution detection systems whose needs are quite different from detection systems in airplanes and helicopters. As we will see, radar systems are difficult to implement in a small footprint due to the need for antenna arrays to have a small detection spot size. In such cases, LiDAR is a better option.

Limitations of radar systems

Radar has traditionally been used to detect airborne targets. The key advantage of radar is its immunity to inclement weather conditions such as rain or fog, which are often the source of accidents. Most airplanes use conformal phased array antennas positioned on the plane's nose to create directed, continually scanning radiation beams that 'see' ahead of them. This is a mature technology that has proven effective on multiple generations of military aircraft.

The underlying issue with radar technology, however, is its resolution and enormous spot size. A radio signal can identify features as small as half its wavelength. Higher frequencies provide improved resolution, but signal propagation via the atmosphere is distance limited. Antennas can be arranged to increase signal strength and overcome propagation loss, and then directed using electrical phasing techniques. However, this strategy is not suitable for drone applications since it necessitates a high number of antennas, which increases the size and expense of the system. A power line in the flight path, for example, is difficult to detect effectively using radar.

You can earn a 1 month paid subscription by recommending just two people to this publication using the button below.

Pros and Cons of LiDAR and Radar Systems

LiDAR is a light sensing technology that has been widely utilized for creating topographical maps of vegetation and mapping archaeological sites, but it has never seen broad use in airborne applications. It is often employed in autonomous vehicles with a sensing range of less than 300m. Radar is frequently a preferable alternative for aerial applications since its detection range should be greater than 1,000m; LiDAR has historically been unable to achieve this due to a variety of technological constraints. One reason for this is that time-of-flight (ToF) LiDAR, which uses reflected light to detect an object, is limited by the signal's round-trip propagation delay and limits the scan rate of the LiDAR system.

For example, at 1500 meters, the round-trip delay is 10 microseconds, limiting the pulse rate to 100 kHz. As a result, only sparse samples are obtained from the detection region, resulting in a low-resolution image. Adding more LiDAR channels and staggering the received pulses will increase power consumption and costs. LiDAR has another significant restriction that radar does not: it is vulnerable to rain, fog, and dust because it relies on light for detection.

The figure below illustrates the disadvantages of both LiDAR and radar systems. The detection spot size of LiDAR is tiny, yet the slow pulse rate causes objects to be totally ignored during detection if they are in the dead zone between pulses. Radar does not miss the object because of its large detection spot size, but the detection resolution is low. It cannot, for example, tell the difference between a power-line and a fence.

Making LiDAR work for long range airborne applications

To make LiDAR function for aerial applications, closely emulate the behavior of a human pilot. Because the human eye has a limited field of vision, pilots are taught to constantly move their heads to'see-and-avoid' any obstructions.

However, putting a laser source on a mechanical servo to simulate this behavior in a LiDAR system is frequently limited by the mechanical system's ability to scan quickly enough or modify the scanning speed on demand. Human vision is just more attractive because it includes both a coarse adjustment at the neck and a highly responsive fine adjustment at the eyeball.

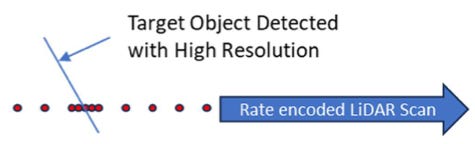

Instead of attempting to swiftly change the direction of the laser source, a more efficient technique to accomplish this electrically is to vary the firing rate of the LiDAR light source. When a target object is discovered, a series of laser pulses are quickly fired to improve resolution on demand.

This, however, presents a distinct concern: when the rapidly fired pulses are reflected from the target object and returned to the receiver, they overlap. This makes it difficult to identify the source of each pulse and recreate the detection scene. To address this uncertainty, Fathom Light employs a laser pulse train encoded with a distinct temporal signature, allowing the receiver to discern between received pulses via matched filtering.

The LiDAR scanning algorithm used to emulate the see-and-avoid method used by human pilots is the core of the high resolution detection system used by Fathom Light.

Here is how it works:

The prototype uses a gimbal system1 that moves the laser source and scans the field-of-view with a 0.3° resolution in the horizontal and vertical axes. This achieves situational awareness.

Laser firing rate is increased for distant objects. Nearby objects are sampled coarsely, and far off objects more finely.

The scan of the last row determines the laser firing rate for the next row. If an object like a power-line is detected, then the firing rate is increased to improve spatial resolution and avoid under-sampling the object.

If laser reflections are sparse, then the algorithm creates staggered bursts along each scan line to search for small objects.

So what kind of lasers are capable of firing high power pulses that can also be rate-adjusted dynamically?

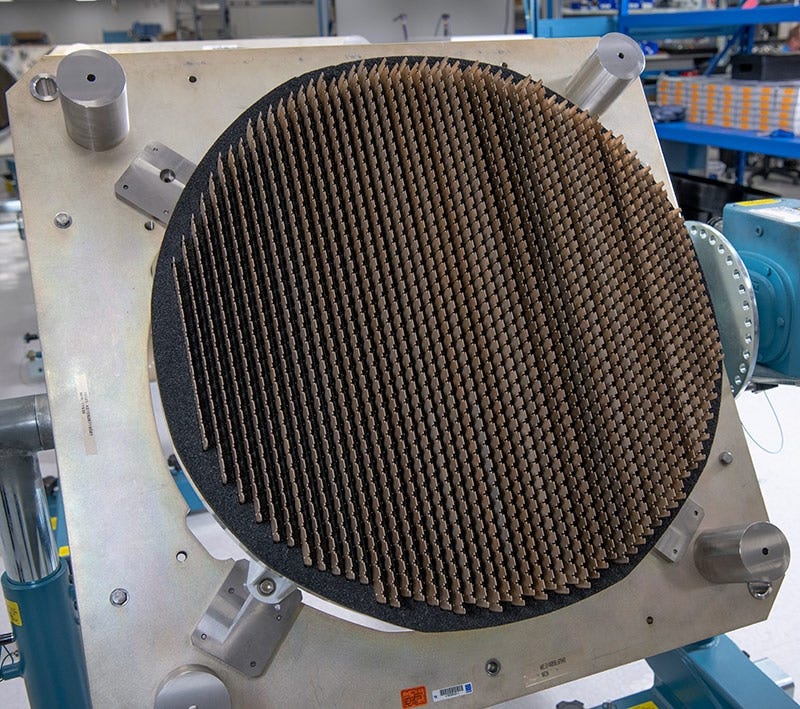

Neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet (Nd:YAG) lasers are a great choice that produce an average power of 1W+ while offering a pulse frequency of ~100 kHz and a pulse width of <10 nanoseconds. Nd:YAG is a well known, widely used, ‘Q-switched’ laser.

A Q-switched laser produces short, high-energy pulses of light by storing energy in its resonator—where Q stands for quality factor—and releasing it in intense bursts lasting nanoseconds. During Q-switching, a device temporarily blocks light emission, letting energy build up before releasing it all at once in a powerful pulse.

Fathom Light’s LiDAR system operates at a wavelength of 1.3 microns because it provides good transmission through the atmosphere.

Demonstration of Long-Range LiDAR Detection

It is easier to show rather than tell, when it comes to LiDAR detection.

Below is Fathom Light’s LiDAR reconstruction of a landscape scene. The red areas show far away objects and the blue regions show nearby ones. Notice how it captures some relatively fine features like the gazebo posts quite well.

Here is the laser system’s birds eye view of a forest canopy compared to the Google Earth view. The yellow dot on the lower left of the Google satellite view shows the approximate position of the laser source. The laser scene rendering shows the system is capable of detecting objects over 1.5 km away. The system is quite likely capable of more, but the data for this scene was arbitrarily restricted to 1.5 km.

Earlier, we looked at why power line detection is important for unmanned drones. Below is Fathom Light’s LiDAR system accurately mapping out power transmission lines in 3D, and can easily do so out to at least half a kilometer out.

The marine scene below with LiDAR point cloud overlaid on it is another demonstration of Fathom Light’s long range detection capability. Note how it can detect points nearly 2 km away while also resolving small objects like buoys.

If you’d like to see video flythroughs of all this LiDAR data, then check out the video below; it’s really quite impressive.

Long-range detection technology using LiDAR offers a lot of promise for both manned and unmanned aircraft systems, and Fathom Light is actively collaborating with avionics companies to develop hardware beyond the prototype phase. If you would like to know about Fathom Light, please reach out to them via their website.

The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in this newsletter are solely mine; they do not reflect the views or positions of my past, present or future employers or any entities I am affiliated with. The content provided is for informational purposes only and does not constitute professional or investment advice. As always, do your own research.

The gimbal system is for demonstration purposes only. The actual implementation on commercial platforms will use different hardware depending on the application.