How Automotive Radar Measures the Angle of Arrival of Objects

How MIMO radar antennas detect the direction of objects in three dimensions.

Hey, I’m Vikram 👋!

I hope you have been enjoying the automotive radar series we have had going this month. If you can, drop me an email and let me know what you think! To quote the song Last Hope by Paramore, “It's just a spark but it's enough to keep me going.”

If you like the content, please click ❤️ on Substack and subscribe! Sharing the article on social media is a great way of supporting this publication.

Note: This article may be truncated in email. Please view it directly on Substack by clicking on the title.

In this article, we continue the discussion on automotive radar. Previously, we looked at how chirp signals are used to measure distance or range of objects. A lot of the fundamentals of frequency modulated continuous wave (FMCW) radar are covered in the article below.

Next, we looked at how to estimate velocity using the phase of the intermediate frequency (IF) signal using a two dimensional Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) that computed individual FFTs to estimate the range (across the fast time axis) and velocity (across the slow time axis). The concepts in the article below are essential to understanding the measurement of angles of arrival with FMCW radar.

Here, we will focus on the estimation of angle of arrival of objects using multiple antennas. Specifically we will cover:

3D radar data, or radar cuboid

How angle of arrival is estimated

Improving angular resolution

The Angle FFT

Use of MIMO for radar

Read time: 10 mins

Understanding the Radar Cuboid

Let’s say there is a transmitting antenna that emits a chirp frame which reflects off an object located far away, and is received by multiple antennas each spaced a distance p apart. For our discussion, it does not matter if the object is moving or stationary. Our purpose is to evaluate the angle of the object to the radar receiver.

Just like before, a received chirp is converted to IF, digitized by the ADC and an in-line FFT is calculated by the hardware accelerated, FFT-optimized radar chip on board the system. On the first axis, we get the range FFT from which we can identify the peaks to directly relate the IF signal frequency to distance. The size of this dimension depends on the FFT length used to calculate range (like 256 or 512).

Remember that we are collecting data simultaneously on multiple antennas. So along the second axis will be the range FFT for each antenna, per chirp. In other words, along the second axis, at any point in time, you will have range FFT data corresponding to any given antenna, for a particular chirp. The size of this dimension depends on how many receiving antennas are present (like 3 or 4).

On the third axis, you will have range FFT data corresponding to each antenna, for every chirp in the frame. Along this axis, doppler FFT is calculated to extract the velocity of the objects in the radar field of view. The size of this dimension depends on how many chirps there are in a frame (like 128 or 256).

If you visualize the data collected along these axes, for every chirp transmitted, the received data is a radar cuboid1 containing range, velocity and angle information. In essence, this is the basic data structure received by the radar receiver for every frame. This entire block of data needs to be collected and stored before it can be used to fully identify objects in the radar field. As a result, radar systems have sufficient on-board memory to store these data blocks before processing.

Estimating Angle of Arrival

Let us simplify our analysis to the case where there are only two receiving antennas. Depending on the location of the object, the chirp signal will travel an extra distance Δp to one antenna compared to the other.

If the distance between the antennas is p, then Δp=psinθ. From the last article, we know that an extra distance Δp results in a phase shift Δϕ given by

where λc and fc is the signal wavelength and frequency respectively.

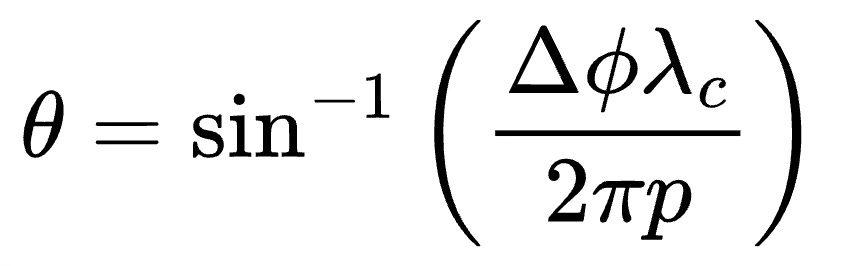

We can calculate the angle of arrival from the phase shift between the signals of the two antennas.

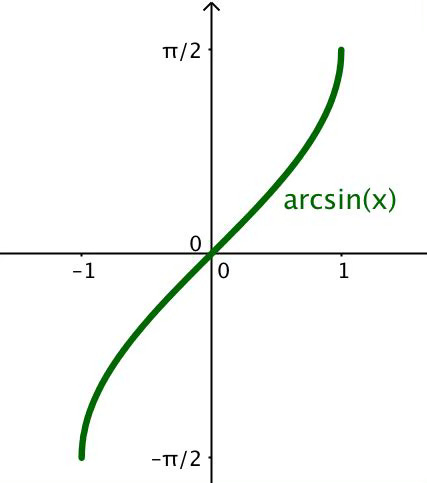

While velocity measurement from phase shift was a linear relationship, the measurement of angle of arrival is not. The inverse trigonometric relationship makes it inherently nonlinear. The relationship between phase shift and angle of arrival is quite linear for angles close to zero degrees, and becomes insensitive as the angles approach ±π/2.

The angle of arrival estimation is most accurate when the object's location is somewhat in front of the receiver antenna, and gets less accurate for wider angles.

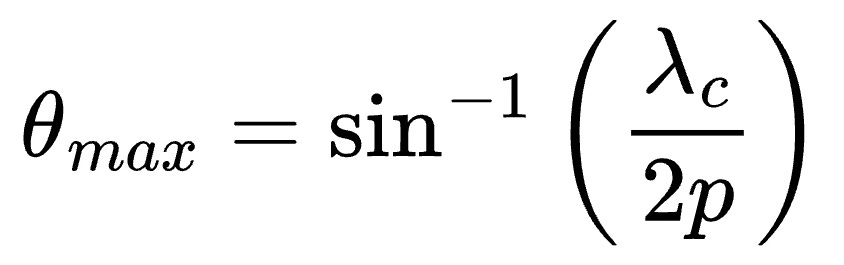

Similar to the case of velocity measurement, the phase shift between antennas is unambiguous only if the total phase shift is less than π radians. Setting Δϕ=π in the above equation gives the maximum field of view of the multi-antenna system.

Spacing the antennas half a wavelength apart (p=λc/2) gives the maximum field of view, θmax = ±π/2. This is the same condition needed in antenna arrays to form constructive and destructive interference patterns and produce focused beams with minimal grating lobes (strange huh?).

Receive antennas placed half wavelength apart gives maximum field of view.

The Angle FFT

Looking back at velocity estimation, we saw that two chirps were insufficient to resolve velocity because there was no way to tell how much phase shift could be attributed to each object at the same range. We had to use multiple chirps and then compute FFT.

Similarly, for two objects at the same range and moving at the same velocity, two antennas are insufficient to unambiguously resolve angle of arrival. Having more antennas in the receive array will help resolve angle of arrival with certainty.

Each antenna in the array is capable of angle and velocity estimation of the object using a range and doppler FFT (2D FFT). Such an FFT allows us to create a range-doppler plot whose peak identifies the object's distance and speed on a two dimensional plane.

Just like how the range FFT peak had a phase component to it that we used to identify velocity in the last article in this series, the 2D FFT peak also has a phase component that allows us to estimate angle of arrival.

Taking an FFT across the 2D FFTs created for each antenna channel in the array will result in peaks corresponding to each object in the radar field of view. The angular velocity of the peaks can then be used to uniquely identify the angle of arrival of each object.

In case you've been counting, to resolve the range, velocity and angle of arrival of objects in an FMCW radar, we need a 3D FFT across all the data contained in a radar cuboid.

Improving Angular Resolution

Adding more chirps in the frame helped increase velocity resolution of the radar. Intuitively, adding more antennas in the array should help increase angular resolution. So how many antennas do we need? What is the minimum angle we can resolve?

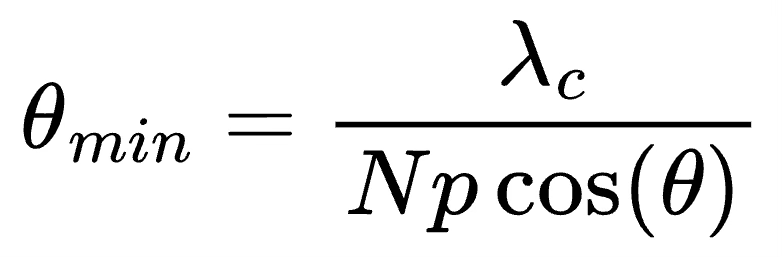

From basic FFT principles that we also used in velocity resolution calculations earlier, the minimum angular velocity that can be resolved is 2π/N, where N is the size of the FFT, or in this case, the number of receive antennas.

After some trigonometric magic2, the minimum angular resolution is calculated as

N times p is just a measure of how large the antenna array is. Larger the antenna array, the better the resolution. This is similar to what we saw in velocity resolution. The longer the chirp signal repetitions, the better the velocity resolution.

Also the angle resolution depends on the angle itself, and is best right in front of the antenna when θ=0, or cos(θ)=1.

Angle resolution degrades as the angle of arrival increases.

If the antenna spacing p is half-wavelength, then the minimum angular resolution in front of the antenna is simply given by

Increasing the number of antennas improves resolution of angle of arrival.

MIMO Antennas for Radar

From the last section, doubling the number of antennas cuts the minimum angle resolution in half. But simply doubling the number of receive antennas is wasteful because every antenna channel needs amplifiers, mixers, filters and ADCs to handle the range-doppler generation. There is a cleverer solution.

The figure below shows the relative phase shift at each antenna element of an eight element receiver array, with one transmitting antenna, from which an angle FFT can be calculated to estimate the angle of arrival. Instead, the same phase shifts are achieved by just adding a transmitting antenna and using only four receiving antennas.

With four receive antennas, the key trick is to space the transmit antennas out by a distance 4p, where p (=λc/2) is the distance between the receive antennas. As a result, the signal from the second transmit antenna travels an extra distance of 4psin(θ). Due to this cleverly designed delay, the signals from the second transmit antenna arrives only after reflections of the transmitted signal by the first antenna have reached all receive antennas. This way, the same phase shifts are obtained as in the eight receive antenna case, but in sequence.

In general, with proper spacing, T transmit antennas and R receive antennas can be designed to be equivalent to T x R receive antennas with a single transmit antenna. These "virtual" antennas created are simply a reuse of the existing ones by appropriately ordering the received signals. This allows the hardware for each antenna channel to be reused, and fewer overall antennas.

For multiple transmit antennas to work, we need to know which transmit antenna signal the received signal corresponds to. There are two popular approaches used to separate signals from different transmit antennas:

Time Division Multiplexing: Separation in time is easy to understand. One antenna first sends out chirps, and then the other. The range-doppler FFT at the receiver is then performed for each transmit-receive antenna pair.

Binary Phase Multiplexing: The phases of the transmitted chirps from each antenna are separated by 180 degrees, which is equivalent to multiplying chirps by +1 or -1. Compared to the time-division approach, using binary phases gives higher signal-to-noise ratio at the receiver since all antennas are transmitting at all times.

This multiple-input multiple-output (MIMO) antenna arrangement can be made even in two dimensions, which allows for angle of arrival estimation in both elevation and azimuth (up/down and side-to-side). The figure below shows alternate MIMO antenna arrangements in linear and two-dimensions.

Finally, if you want to see an FMCW radar in action, then check out this video.

References

Check out these really good set of FMCW radar videos from Texas Instruments (link).

This white paper from Texas Instruments covers some aspects of angle estimation (link).

The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in this newsletter are solely mine; they do not reflect the views or positions of my employer or any entities I am affiliated with. The content provided is for informational purposes only and does not constitute professional or investment advice.

Literature calls it a Radar Cube, but I refuse to use that nomenclature because it implies all dimensions of cube are the same. It is almost never so. A more accurate term is cuboid, even if it does not roll off the tongue.

Find the phase change due to a small change in arrival Δθ, and equate it to 2π/N. You will need to use the finite difference approximation to derivative of a sine, which is cos. Trigonometric magic, but not too much. Try deriving it over a morning coffee.

Really enjoyed this. Thank you. What was the catalyst for this sequence?